I have always loved carnations and was longing to find time to write a blog post about them. I have never understood the bad reputation of these flowers: they last for weeks, are budget-friendly and I find their ruffled petals extremely beautiful. They are also Spain’s national flower so my carnation obsession might have something to do with that.

They were introduced in Spain by Emperor Charles V who gave the ‘Persian Flower’ as a present to his wife Isabel of Portugal while they were in La Alhambra, in Granada. Shortly after, Charles V ordered that carnations should be planted in all the gardens of the Alhambra. Over time this flower expanded throughout the southern part of Spain, adorning gardens, courtyards and balconies as well as the hair of women dressed in flamenco dresses.

But carnations, members of the Dianthus family, have been cultivated for at least 2000 years. Wild Dianthus caryophyllus is likely to have originated from the Mediterranean regions of Greece and Italy (including Sicily and Sardinia), but the long time in cultivation makes it difficult to confirm its precise origin. The genus Dianthus contains several species that have been cultivated for hundreds of years for ornamental purposes.

It was the Athenians that named the flower Dianthos, from the Greek words dios (divine) and anthos (flower). Gillyflower, another name by which the plant is known, probably came from the French who called dianthus, gelofre. Carnations probably originated in the Pyrenees as single flowered specimens, but none of these naturally occurring, single wild varieties exists today. The beauty of its flower, its longevity as a cut flower and the ease with which it could be cultivated combined gave it instant popularity in many cultures.

The plant was subjected to massive breeding programs and by the early 1700’s there were single, semi-double and double carnations available in crimson, blush, purple, red, scarlet, white and tawny colours There were also striped, stippled, spotted and veined carnations with smooth or picoteed petal edges. Many of these hybrids were divided into very specific classes: Bizarre, Flake, Flame and Picatee.

Since Victorian times, when the interest in botany went hand in hand with the interest in the ‘language of flowers’ Carnations symbolize love, affection and fascination.

Quoting Caroline Roehm (a fellow carnation lover) ‘there are no bad flowers, only people who do them badly’ I hope this blog post and the images below inspire you to embrace the simple beauty of carnations.

Henri Fantin Latour, Carnations without vase, 1899

Henri Fantin Latour, Carnations without vase, 1899

Georg Flegel, Still life with carnation and eggs, 1600

Georg Flegel, Still life with carnation and eggs, 1600

Persian Flower Hand-painted tumblers

Persian Flower Hand-painted tumblers

El vendedor de claveles, (The carnation seller) Francisco Bayeu y Subias, Museo Nacional del Prado, 1786.

El vendedor de claveles, (The carnation seller) Francisco Bayeu y Subias, Museo Nacional del Prado, 1786.

Tile with two carnations and foliage, William de Morgan, c.1881, The British Museum

Tile with two carnations and foliage, William de Morgan, c.1881, The British Museum

Blue carnation with prunus leaves, William de Morgan, 1872-1907, De Morgan collection

Blue carnation with prunus leaves, William de Morgan, 1872-1907, De Morgan collection

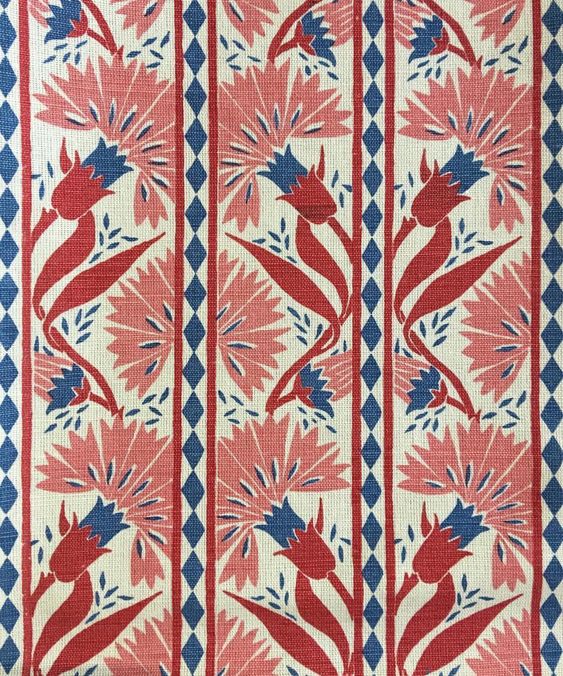

Carnation stripe fabric by Bernard Thorp

Carnation stripe fabric by Bernard Thorp

An Iznik polychrome pottery dish with carnation bouquet, Turkey, circa 1580, Sotheby’s

An Iznik polychrome pottery dish with carnation bouquet, Turkey, circa 1580, Sotheby’s

María Ana Victoria de Borbón, niña (futura reina de Portugal), Jean Ranc, Museo Nacional del Prado, 1725.

María Ana Victoria de Borbón, niña (futura reina de Portugal), Jean Ranc, Museo Nacional del Prado, 1725.

The book of carnation, R.P. Brotherson, Martin R. Smith

The book of carnation, R.P. Brotherson, Martin R. Smith

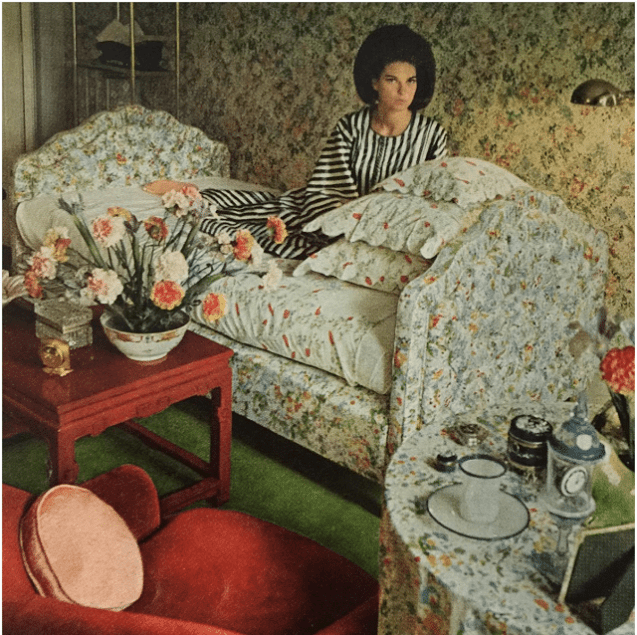

Louise Savitt’s bedroom. Horst 1965.

Louise Savitt’s bedroom. Horst 1965.

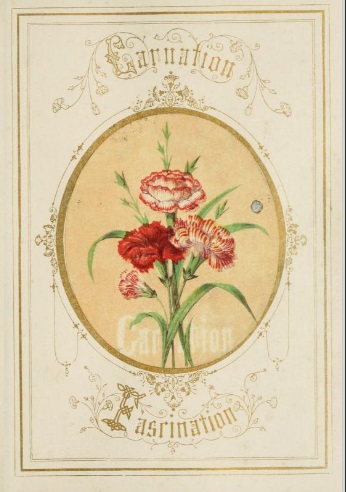

The Language of Flowers: An Alphabet of Floral Emblems (London; New York: T. Nelson and Sons, 1857)

The Language of Flowers: An Alphabet of Floral Emblems (London; New York: T. Nelson and Sons, 1857)

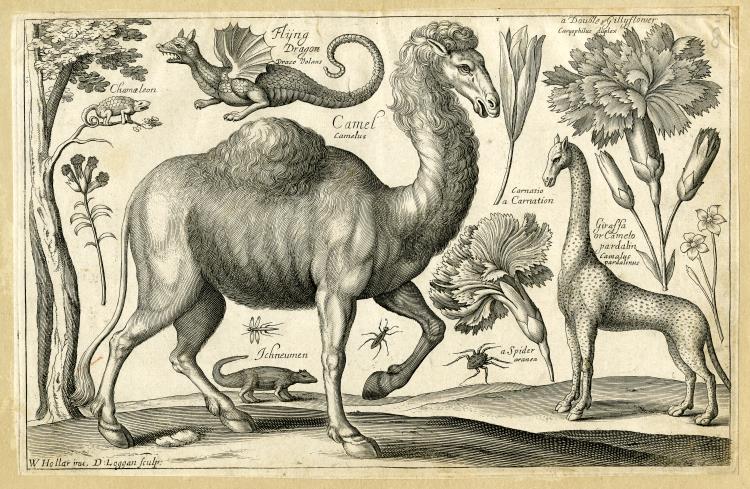

Animalium, Ferarum, & Bestiarum (A camel, giraffe, chameleon in a tree, flying dragon, ichneumon, spider, and various insects and flowers, including a carnation) print; Wenceslaus Hollar (After); David Loggan print made after Wenceslaus Hollar. 1662-1663; The British Museum.

Animalium, Ferarum, & Bestiarum (A camel, giraffe, chameleon in a tree, flying dragon, ichneumon, spider, and various insects and flowers, including a carnation) print; Wenceslaus Hollar (After); David Loggan print made after Wenceslaus Hollar. 1662-1663; The British Museum.

Gitana con claveles, (gipsy with carnations) Santiago Martínez, 1919

Gitana con claveles, (gipsy with carnations) Santiago Martínez, 1919

D. Portahult ‘Oeillets’ (Carnation) collecion

D. Portahult ‘Oeillets’ (Carnation) collecion