If you see me in summer, chances are—most likely—I’ll be carrying a fan in my bag or hand. In Spain, the fan is more than just an accessory; it’s part of our cultural identity. Growing up, I watched the ladies around me carrying all summer long. I remember being mesmerised by the rhythmic movements, and the silent yet expressive language of the abanico.

The use of fans dates back thousands of years. In ancient Egypt, large palm-leaf fans were not only tools for cooling but also symbols of divine power, often seen in the hands of pharaohs. The Chinese and Japanese perfected the art of folding fans (sensu and ōgi), using paper, silk, and intricate designs that became status symbols.

By the Renaissance, fans had become fashion statements across Europe, thanks to trade with Asia. They evolved into elaborate accessories made of lace, ivory, and gold, often hand-painted with romantic scenes. By the 18th and 19th centuries, the fan was an essential element of European aristocratic fashion, used by ladies to communicate secret messages through a coded ‘fan language’ a subtle flick could mean ‘I’m interested’, while a quick close might suggest ‘I’m not impressed’.

Spain became a major centre for fan production in the 18th and 19th centuries, with artisans crafting exquisite designs. Valencia and Seville, in particular, became famous for their skilled fan makers, a tradition that continues today.

The art historian in me felt the need to do a round-up of some of my very favourite fan moments in art

La Dama del Abanico, (Lady with a Fan) Alonso Sanchez Coello, 1570, Museo del Prado

The lady in this portrait is holding a folding Japanese-style fan, nod to the customs and portrayals of women from Portugal, where the first Oriental fans arrived in the late fifteenth century. The links by marriage between the courts of Madrid and Lisbon brought this accessory to Spain and other European capitals. Fans soon became a part of every noble woman’s vestments, as well as an instrument of courtship and flirtation and an indicator of social standing; they joined the traditional handkerchiefs and missals held by elite sitters for portraits.

El vendedor de abanicos ( The Fans Seller) Jose del Castillo, 1786, Museo del Prado. Cartoon for tapestry.

A street vendor displays the fans he is selling to a young woman seated on the ground.

The Green Fan (Girl of Toledo, Spain), by Robert Henri, 1912, The Gibbes Museum

Robert Henri (1865-1929) was one of the most influential American artists of the early 20th century. A leading proponent of the urban realist style that characterized the art of the Ashcan School, Henri was widely celebrated as a painter and a teacher. He travelled to Spain seven times between 1900 and 1926 and produced a substantial body of work inspired by the country’s citizens and culture. His portraits present a dazzling cross-section of Spanish society—famous dancers, dashing bullfighters, spirited gypsies, blind street singers and weathered old peasants—as he masterfully captures the spirit of unique individuals.

Still Life with a Fan, Vanessa Bell, c.1932, Philip Mould & Company

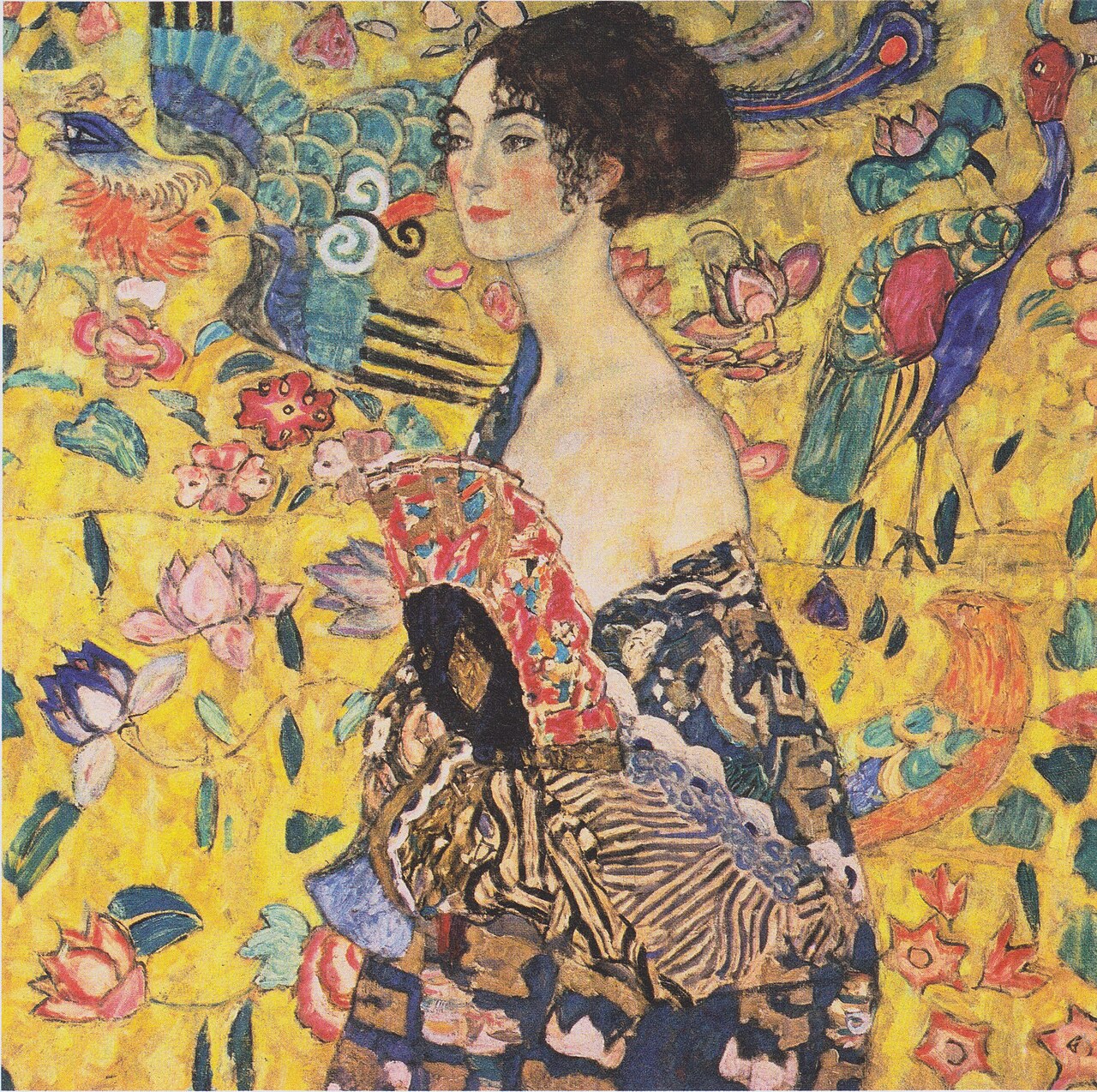

Lady with a Fan, Gustav Klimt, 1917 , Private Collection

Lady with a Fan is the final portrait created by the Austrian painter Gustav Klimt. Painted in 1917, the uncommissioned piece depicting an unidentified woman was on an easel in his studio when he died in 1918. Like many of Klimt’s late works, it incorporates strong Asian influences including many Chinese motifs.

In June 2023, it sold at auction with Sotheby’s in London for £85.3 million, the highest price ever achieved in Europe for a work of art. It was bought by art dealer Patti Wong on behalf of a Hong Kong collector.

As I embark on my fan rabbit hole I discover an article by Joseph Addison for The Spectator in 1711 in which the core point is how society (especially fashionable women) has turned the fan- a simple, functional object into a complex language and almost theatrical performance. But underneath the humour, Addison is making a larger point about how artificial and performative social life had become in his time. He’s fascinated by how the fan — meant to cool or provide comfort — had been transformed into an elaborate tool for flirtation, secrecy, and silent communication in polite society. He’s not angry about it — on the contrary, he seems delighted and amused — but he’s also poking fun at how highly trained and exaggerated these rituals are. Below is an extract from the article.

‘Women are armed with Fans as Men with Swords, and sometimes do more Execution with them’

Handle your Fans,

Unfurl your fans.

Discharge your Fans,

Ground your Fans,

Recover your Fans,

Flutter your Fans.

It’s also researching for this blog post that I discovered there’s a fan museum in London! It’s in Greenwich and I cannot wait to visit it this spring. After entering the website and seeing the history and the people behind it, Hélène Alexander MBE (a world authority on fans) and her late husband, ‘Dickie’ A.V Alexander OBE makes me even more excited to my visit, Gathered from across the world, the collection spans more than 1,000 years of fan history and culture. Here are some of the gems in their collection.

Advertising fan for Carlton Hotel and Restaurant, London, c.1900

Horn Brise Fan c.1820s

Japanese Folding Fan, Brisé with Silk Streamers

Chinese wood fan with silk. c.1860

I had planned to include a section on some of Spain’s most iconic fan makers, but this post is already turning into quite the fan anthology — and I’m enjoying the research far too much. I’ll save that for part two, coming soon. In the meantime, I’d love to hear if you have a special fan or a story worth sharing.

Loved this post Gloria! You are a wonderful writer and researcher. I think it is time you went for a Masters in Art History. Xx Liz Downing