Tulip season is a major event in Holland. Part of the country is transformed into a vast sea of flowers from mid-March to mid-May. It starts with crocus season in March, which is followed by daffodils and hyacinths. Finally, the tulips show their gorgeous colours, this is from mid-April through the first week of May. This flower originally came from Turkey but has become Holland’s symbol. How did that happen?

The Tulip was actually originally a wildflower growing in Central Asia. It was first cultivated by the Turks as early as 1000AD. Although the Dutch Tulipomania is the most famous, The first mania occurred way back in 1500’s in Turkey – which was the time of the Ottoman Empire and of Sultan Suleiman I (1494-1566). Tulips became highly cultivated blooms, developed for the pleasure of the Sultan and his entourage. During the Turkish reign of Ahmed III (1703-30) it is believed that the Tulip reigned supreme as a symbol of wealth and prestige and the period later became known as ‘Age of the Tulips’.

An Iznik Polychrome tile, Turkey, circa 1575 of square form painted in underglaze cobalt blue, viridian green, turquoise and relief red, outlined in black with tulips, saz and composite lotus and saz palmettes issuing from scrolling tendrils. Sotheby’s

An Iznik Polychrome tile, Turkey, circa 1575 of square form painted in underglaze cobalt blue, viridian green, turquoise and relief red, outlined in black with tulips, saz and composite lotus and saz palmettes issuing from scrolling tendrils. Sotheby’s

It was during the early 1700’s that the Turks began what was probably the first of the Tulip Festivals which was held at night during a full moon. Hundreds of exquisite vases were filled with the most breath-taking Tulips, crystal lanterns were used to cast an enchanting light over the gardens whilst aviaries were filled with canaries and nightingales that sang for the guests. Romantically, all guests were required to wear colours which harmonised with the flowers.

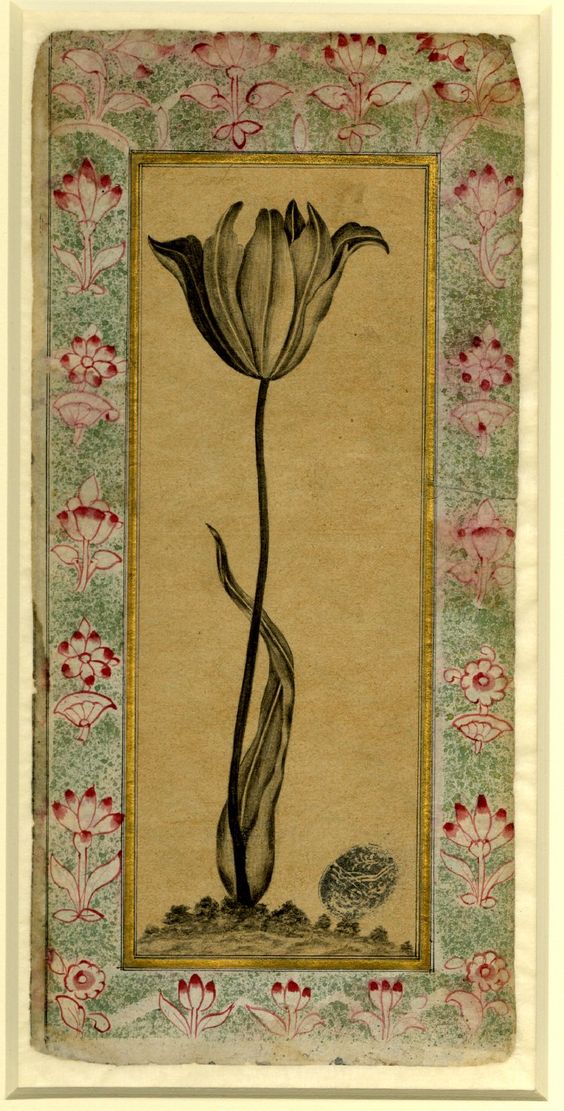

A tulip in a landscape within stencilled borders. Ottoman, 17th century. British Museum Collection.

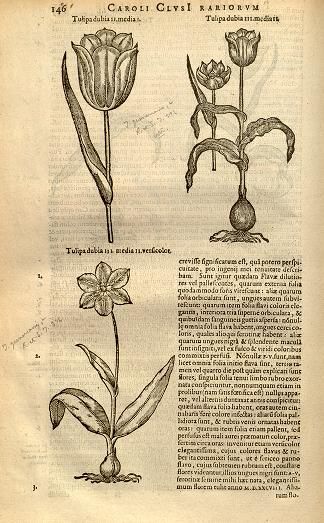

Tulips were imported into Holland in the sixteenth century. When Carolus Clusius wrote the first major book on tulips in 1592, they became so popular that his garden was raided and bulbs were stolen on a regular basis.

Tulips were originally a natural curiosity and a hobby for the extremely rich. The fascination with the tulips, its endless mutations and mystery, gave it an increasing value of immense proportions.

Double Portrait of a Husband and Wife with Tulip, Bulb, and Shells oil on panel painting by Michiel Jansz van Mierevelt, 1609 Sotheby’s

Speculation on Tulip bulbs began building quickly as the middle and upper classes sought them as the ultimate symbol of wealth and prosperity. Along with aviaries of exotic birds and large, decorative fountains, there would always be Tulips in the garden of any self-respecting Emperor, King, Prince, Archbishop or member of the aristocracy. Often mirrors would be set up in the garden to give the illusion that the owner had been able to afford to plant many more tulips than he actually had.

Until 1630 the bulbs were grown and traded only between connoisseurs and scholars but more commercially minded people soon noticed the ever increasing prices being paid for certain Tulips and thought they’d found the perfect “get rich quick” scheme.

And so the popularity of the Tulip increased and more and more people became caught up in the trade.

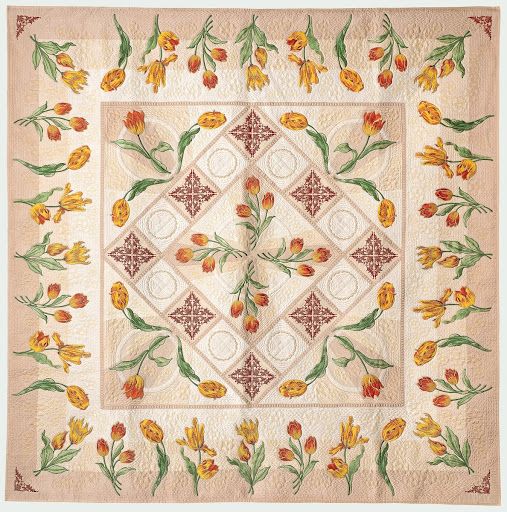

It wasn’t long before the majority of the Dutch community became obsessed with these flowers. Those who could not afford the bulbs settled instead for art, furniture, embroideries and ceramics which featured the flowers.

Tulip vase, Adriaen Kocks, 1694. Royal Collection Trust, UK. Many of Queen Mary II’s Delft vases were described in the inventories of her palaces at Het Loo and Hampton Court as standing on the hearth. Flower vases such as these were used to ornament the fireplace during the spring and summer when fires were not lit. Each of the nine hexagonal stages was made separately, with a sealed water reservoir and six protruding grotesque animal mouths, into which the cut stems of tulips or other flowers could be placed.

Many of the gorgeous Tulip watercolours painted during this period are now considered works of art but were, at the time, painted for catalogues with which to tempt buyers into ever more extravagant purchases. It was only ever the most expensive Tulips (ie those with ‘broken’ colour) which were painted.

Since bulbs were sold by weight, most people were speculating on the future weight of the bulb once it was dug.

Jacob Marrel, Four Tulips: Boter man (Butter Man), Joncker (Nobleman), Grote geplumaceerde (The Great Plumed One), and Voorwint (With the Wind), ca. 1635–45. Met Museum.

The tulip’s popularity reached unprecedented, even excessive, heights, in the 1630s. This gave rise to a veritable tulipmania, which held many Dutchmen in its grip in 1636 and 1637. If the flower had initially roused largely scientific interest, from around 1630 on tulips became attractive financially. Tulips and tulip bulbs were bought and sold actively, frantically in fact, and this trade deteriorated into speculation in 1637. Countless people jumped on the bandwagon buying options they could pay later, some even putting up their homes as collateral. The market crashed suddenly in February 1637; prices plummeted and many investors were left penniless.

Tulip, two Branches of Myrtle and two Shells, Maria Sibylla Merian (attributed to) c. 1700. Rijksmuseum

Jean Leon Gerome, The Tulip Folly, 1882, The Walters Art Museum

Susan Stewart ‘Tulip Fire’ Quilt, 2012, The National Quilt Museum

The people who speculated in tulips and tulip bulbs were the object of ridicule in countless pamphlets and prints. After all, vast sums were involved. Yet this way of doing business existed already in the 16th century, for instance in the grain trade. This was called grain futures, which is a polite word for speculation. Futures trading is still current; our present-day options exchange continues to work with a form of futures.

While interest in tulips remained undiminished after the crash in 1637, the market was no longer rife with excess and prices dropped to a more reasonable level. Tulips never lost their popularity, and growers in the west of Holland have continued to develop new varieties to this very day.

‘Some tulips last so long you could almost dust them off, and others you can’t trust overnight’ Constance Spry